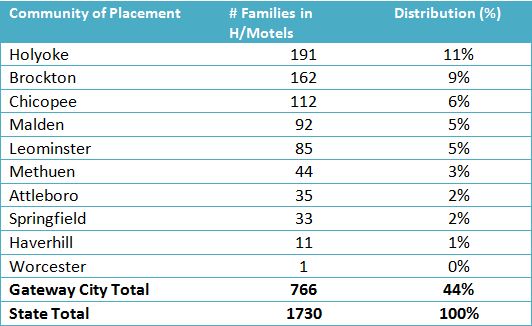

Since 2009, the number of homeless students in Massachusetts has nearly doubled. As the crisis has grown, a lot of attention has been placed on the number of homeless families living in motels for relatively long stays at a high cost to the state. Gateway Cities were home to nearly half of the 1,700 families with children living in shelters and motels last year.

Gateway City leaders have sought to draw attention to the disproportionate costs the state’s family homelessness crisis places on their communities. A recent report by the State Auditor’s Office found that Gateway Cities spent more than $3 million in FY 2014 to transport homeless students to school in the community where they were living when they became homeless. The auditor also found that Gateway Cities cover $1.7 million in unreimbursed school expenses and nearly $1 million in lost or forgone local option room excise tax revenue from motels.

A much larger hidden cost is the impact of growing family homelessness on Gateway City school districts. Studies have shown that homeless students have the highest rates of mobility, frequent absences and tardy arrivals, significant educational gaps, and poor medical, dental and mental health care. Furthermore, new students entering schools during the year disrupt the entire classroom, slowing the pace of instruction and lowering academic outcomes for all students.

Gateway City leaders have worked to address this creatively through education policy, as highlighted in the 5DP case study, but what we really need is more attention to student mobility as the state sets housing policy in response to family homeless. In a 2011 policy brief, MassINC explored options for housing policy.

Four years later, there’s growing evidence that housing resources can be used creatively to stabilize families with school-age children. In Tacoma, Washington, for example, a local elementary school experiencing high rates of student mobility partnered with the local housing authority. The pilot offered 50 homeless families with a child enrolled in kindergarten, first, or second grade five years of rental assistance. In return, the families agreed to meet five expectations:

- Keep their child enrolled in McCarver;

- Be very involved with school activities and their child’s education;

- Work on their own career and financial growth;

- Work with The Tacoma Housing Authority staff to accomplish these goals; and

- Share data on their child’s progress in school and the parents’ income gains.

In its third year, evaluators found that the Tacoma program “made considerable progress toward their goals of family financial stability with higher average income, and students have made gains in educational performance.”

As a research assistant at MassINC, I helped prepare the 2011 report on housing policy options to reduce student mobility. Now as a graduate student at Brandeis, I’m looking again at innovative strategies to support unstable families through housing policy. Over the coming months, I hope to gather as many ideas as I can from Gateway City leaders and others with ideas and insights into this problem.

Table 1: Distribution of Hotel Homeless Shelter Costs (FY2014)

* This number is only representative of the 41 communities that submitted data to the State Auditor’s Office. However, these communities were selected based on the size of their past applications for McKinney-Vento transportation reimbursements and/or the presence within these districts of families in state-funded hotel/motel shelter housing in calendar year 2014.

Table 2: Distribution of Families in Shelters/Motels (EA Program, 12.2.2014)