This month marks a major milestone in the longstanding effort to reduce incarceration in Massachusetts. In early June, the number of people held in state and county correctional facilities fell to levels that were half of their tough-on-crime era peak. As we think broadly about strategies to erase yawning racial and ethnic disparities, it is important to take stock of the opportunity a return to lower levels of incarceration affords to make alternative investments in communities of color. These communities have undoubtedly borne the brunt of decades of misguided criminal justice policies. Addressing this legacy will require a serious commitment of resources.

Here’s what the data suggest:

- Prison populations are way down, but they still remain relatively high.

When the COVID-19 crisis hit in March, the number of individuals held in state and county correctional facilities was already down by 35 percent from 2013, thanks in part to the state’s landmark 2018 criminal justice reform law. Efforts to limit the spread of COVID-19 by reducing crowding in correctional facilities has pushed the state’s correctional population down another 15 percentage points. State and county correctional facilities now hold 12,000 fewer people than they did at the 2013 peak.

However, Massachusetts still has approximately 182 residents per 100,000 incarcerated. This rate is approximately double that of most Western countries, and significantly higher than Massachusetts’ incarceration rate prior to the enactment of tough-on-crime policies. In the past, some have argued that Massachusetts will always have significantly higher rates of incarceration as compared to other countries given the prevalence of violence and firearms in our society. However, it is increasingly clear that the heavy use of incarceration and the cycles it perpetuates are deeply enmeshed in policies that undervalue the lives and discount the experiences of people of color.

This reality is evident when considering the size of the state’s prison population in the absence of racial and ethnic disparities. According to 2018 Census data, black residents were 5.5 more likely to be incarcerated than white residents in Massachusetts; Latinos in Massachusetts were 4 times more likely to be incarcerated than whites. If Massachusetts incarcerated black and Latino residents at the same rate as whites, the number of people in state and county correctional facilities would fall by approximately half.

However, it is also notable that policies that lead to higher incarceration rates for people of color also ensnare white residents. The 2018 incarceration rate for white residents (190 per 100,000) was more than double the incarceration rate of most Western countries.

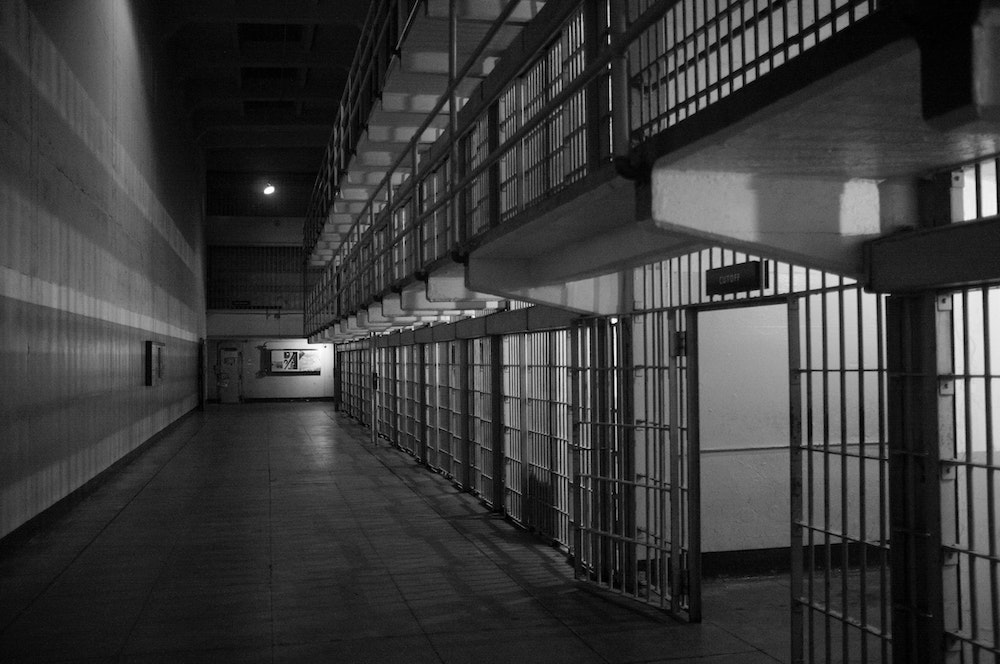

- Massachusetts continues to operate a sprawling corrections system.

All told, state and county correctional agencies maintain a complex of nearly 500 buildings with approximately 10 million square feet among them.

The cost of operating all of these facilities has risen even though they serve far fewer individuals than in the past. Adjusting for inflation, state and county correctional expenditures grew by 6 between FY 2013 and FY 2020, a period during which the population fell by 27 percent. Growing expenditure with a shrinking population pushed the per inmate costs up by 45 percent, from $43,671 in 2013 to $63,314 in 2020.

Despite the steadily declining population, the most recent data for calendar year 2019 show state and county correctional facilities employed an all-time high of 13,000 workers. In addition to this large payroll, Massachusetts taxpayers will need to cover the pension and healthcare costs for these workers for years to come.

- The state’s current fiscal challenges pose a clear threat to public safety in communities of color.

In the past, funding for crime prevention programs have disproportionately suffered deep cuts when the state budget contracted. For example, the line item for gang preventions efforts was cut by more than half from $14 million in FY 2008 to less than $6 million in FY 2010. Funding for summer jobs for at-risk youth was hit even harder, falling from $14 million to less than $5 million over this period. Summer and afterschool programs for disadvantaged youth was the victim of the previous recession. This litem went from $18 million in FY 2001 to zero for a number of years. It finally remerged in a significant way in the current FY 2020 budget, but still only at half the previous level.

Rigorous evaluation shows programs like these prevent crime and victimization, particularly among black and Latino young men. The programs are more necessary now than ever. Massachusetts cannot safely reduce the use of incarceration without provide alternative programs and interventions.

Youth coming of age in communities of color are dealing with the convergence of the most difficult economic downturn in a century, the trauma of a disease that kills their family members at disproportionate rates, and the stress of difficult realities around race and identity.

Now is the time for budget makers to consolidate correctional facilities and extract savings to adequately fund programs that increase the resiliency of youth and their communities.