Massachusetts is projected to add more than a half million new residents over the next two decades. Where these new residents settle will have important consequences for quality of life, the environment, economic growth, and access to opportunity. How we grow will also have critical implications for the fiscal health of state and local governments. Our budgets are already under tremendous strain. Urban infill that concentrates new residents around existing infrastructure with capacity to serve new residents could produce large efficiencies (for more on this, check out Chris Zimmerman’s presentation at the Smart Growth Conference).

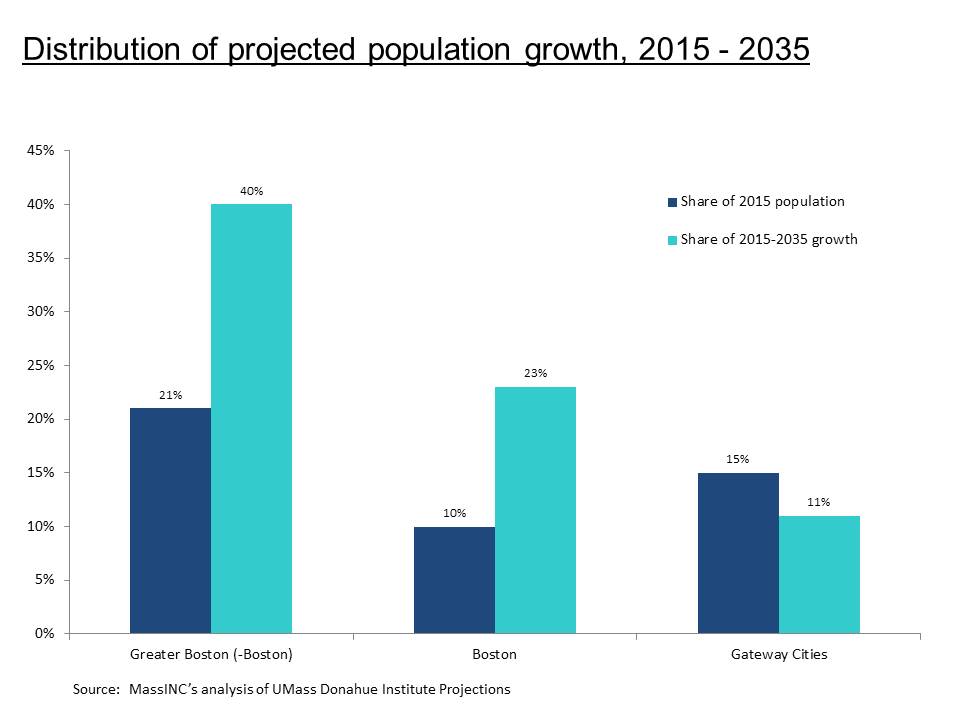

The most recent population projections for Massachusetts—which assume business as usual for development patterns and the public policies that shape them—suggest there will be some urban infill. The City of Boston is currently 10 percent of the state’s population, but it’s projected to pull in 23 percent of growth between 2015 and 2035. However, much of Greater Boston is projected to consume an outsized share of the state’s future growth; suburbs in the area will swallow up 40 percent of the state’s growth, twice their current share of the Massachusetts population. What the projections don’t foretell is reinvestment in our Gateway Cities. The Gateway Cities from MassINC’s 2007 study make up 15 percent of the Massachusetts population today, but the projections have them gaining only 11 percent of the state’s growth over the next two decades. In part, this represents slower growth in the regions where they are situated, but it also assumes that infill is unlikely. Take a close look at the map below: Fitchburg and Worcester aren’t gaining share, but less developed communities all around them expand at above average growth rates. A similar pattern is visible down on the South Coast.

What the projections don’t foretell is reinvestment in our Gateway Cities. The Gateway Cities from MassINC’s 2007 study make up 15 percent of the Massachusetts population today, but the projections have them gaining only 11 percent of the state’s growth over the next two decades. In part, this represents slower growth in the regions where they are situated, but it also assumes that infill is unlikely. Take a close look at the map below: Fitchburg and Worcester aren’t gaining share, but less developed communities all around them expand at above average growth rates. A similar pattern is visible down on the South Coast.

The transformative transit-oriented development project seeks to help us break free from this decades long pattern by leveraging existing transit assets. If we can help Gateway Cities correct the weak market conditions that prevent reinvestment and growth, we can better utilize the transportation network to make mobility and economic vitality in our commonwealth more even and fluid.

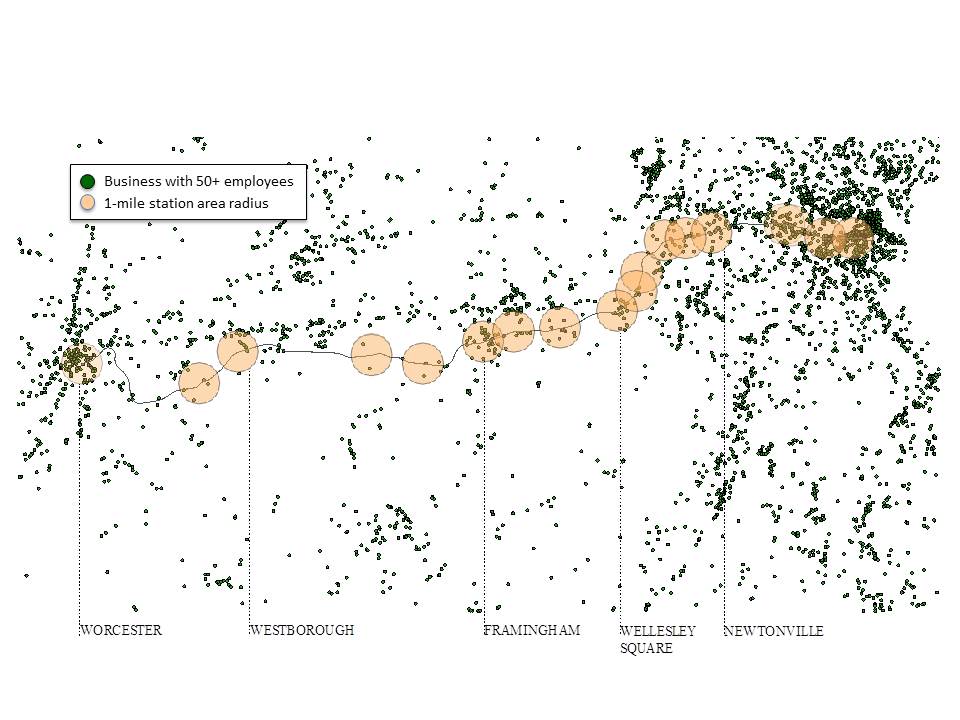

The last map illustrates how much power better mobility could generate for our regional economies. The shaded circles depict a one-mile radius around each station on the Worcester line. The green dots are businesses with 50 or more employees. For the most part, employment clusters along the corridor fall outside of the station areas, making it difficult for people to use transit, unless you live or work in Boston or Worcester (and even then, trip length/service quality presents a major barrier).

But one could envision this rail line becoming a much more regional asset shuttling people from Worcester, Westborough, Framingham, Newton, Wellesley, and Boston. They could live or work in any of these locations and walk or bike quickly to their final destination.

What would it cost to provide such service? What tools would be required to get the kind of build-out in station areas that would maximize return on this service? And what would be the benefits for our economy, our environment, and our quality of life? These are the central questions our study seeks to answer as we explore transformative transit-oriented development’s potential to bend the curve on business as usual growth patterns.