The Honorable William Straus, House Chair

The Honorable Joseph Boncore, Senate Chair Joint Committee on Transportation

State House, Room 134 Boston, MA 02133

via email

Dear Chairmen Straus and Boncore,

On behalf of MassINC’s Gateway Cities Innovation Institute, I strongly urge you to expedite a favorable report on H. 3526, “An Act Relative to Low-Income Transit Fares” along with H. 3403/S. 2340 “An Act Relative to Fare-Free Buses.” These are needed to rebuild transit ridership and increase mobility for residents of Gateway Cities.

Fare policy is a powerful tool that can be used to build ridership and make the system more accessible to residents, or it can restrict ridership, even while trying to improve service. Unfortunately, MassDOT and the MBTA have too often taken the simplistic approach that increasing fares as much as possible creates a healthy transit system and maximizes transportation revenue. We disagree.

There is no doubt that public transit faces a crisis with ridership losses across most modes and routes because of the pandemic. We sympathize with our transportation agencies as they confront unpredictable commuting trends, and we understand their instinct to take a defensive posture.

But socking away federal funds to prop up the status quo while the life slowly drains out of the transportation system for the next five years is not a recipe for success. It’s the right time to invest in a new paradigm of public transportation for an era of independence from fossil fuels. The “bottom line” must consider the societal benefits of clean and convenient transportation as well as the cost of an inconvenient system.

And to do that, our most important value, our North Star, should be to maximize ridership, especially among Massachusetts residents who are most transit-dependent. Chasing other visions, such as a financially self-sustaining transit system, or the notion that premium transit will get professionals out of their cars, are pipe dreams. They may be achievable for certain services, but we should not build our system around them. The heart of the public transportation system are residents without cars, and those who may choose not to purchase a car in the future.

That means providing fixed-route service, both bus and train, that is inexpensive and within the reach of the broadest number of residents. It also means improving service frequency. This is not an either/or choice—we must do both. And yes, it will require increased state investment, but with robust federal funding for the next few years and with opportunities for new ongoing state transportation revenue, the time has never been better to set our sight on the horizon and proceed boldly. If we don’t do it now, our transportation system will hobble along like it has, creaking and groaning, without serving its best customers well.

Instead, we recommend that transit agencies undertake short-term and long-term strategies to build their ridership through fare policies that incentivize riders to return to transit while increasing the daily ridership base. Chasing white-collar workers who are shifting to a hybrid work schedule (which can be done easily enough by creating flexible new ticket products) to build ridership will not be as effective as focusing on transit-dependent populations, like seniors, low-income families, and essential workers. Given the Administration’s misguided preference to finance transit through fares that dampen this core customer base, the Legislature has an important role to play in shaping transit fare policy.

The first step is to pass the Madaro bill (H. 3526). It is unconscionable that the MBTA has not yet implemented a low-income fare program, despite the T’s own Control Board directing staff over the last several years to make it a priority. The Administration has thus far failed to show the leadership that’s needed to coordinate across state agencies to get it done. State programs already exist, with experienced staff, who have the expertise to administer a means-tested transit benefit, and there is no reason why one of those programs shouldn’t form the eligibility basis for a low-income fare. This isn’t something that the MBTA should build from scratch. In fact, they should probably replace their existing discount programs, which rely on photocopies, hand-filled forms, and manually inputted data, making them outdated and inefficient. This is a problem of political will, not know-how.

Commuter rail offers a clear opportunity to serve more low-income riders and increase revenue at the same time. Anyone who lives in a Gateway City served by commuter rail knows that the cost is prohibitive for all but the highest-income residents, and most of the commuters are white-collar workers from surrounding suburbs. In fact, before the pandemic, the MBTA estimated that just 2,000 low-income riders utilized commuter rail because it’s so expensive. For the price of a monthly pass—which may cost over $400/month for many residents—you could lease a luxury vehicle. As of May, 183,000 Gateway City residents remained out of work. The vast majority (110,000) of these unemployed workers live in communities served by MBTA commuter rail. Even if they paid heavily discounted fares, these new riders would provide additional revenue for the system. It makes sense for transit justice and equity, it makes sense for connecting workers to more jobs, it makes sense for filling up the trains.

In fact, even if the MBTA needs time to roll out a low-income fare across all modes, there seems no obstacle to immediately implementing a low-income fare for commuter rail. One example of an interim policy would be for a rider to show their MassHealth card or SNAP card in order to purchase a flat $5 commuter rail ticket for the day, similar to the popular $10 weekend passes that the MBTA has already implemented.

Please report this bill out favorably as quickly as possible in order to launch a low-income fare program in 2022. Let’s not lose another year.

We would also like to express our support for H. 3403 and S. 2340 pertaining to fare-free buses, although we would be receptive to modifications that prioritize RTAs and service in Gateway Cities.

There are two important questions to consider when deliberating on zero-fare bus service:

- How would the fiscal impact affect the transit agency’s ability to provide service?

- Would the cost be worth the investment in terms of the benefit to riders and ridership?

These bills will help us answer these questions by conducting pilot programs across the state and analyzing the results. That is a compelling reason alone to advance them. Another reason is to create a powerful short-term incentive for commuters and others to return to transit in order to bring back ridership to pre-pandemic levels until the public health situation stabilizes.

That being said, we already know a good deal about fares and ridership, which leads us to believe that many Regional Transit Authorities could be ideal candidates for permanent zero-fare bus programs.

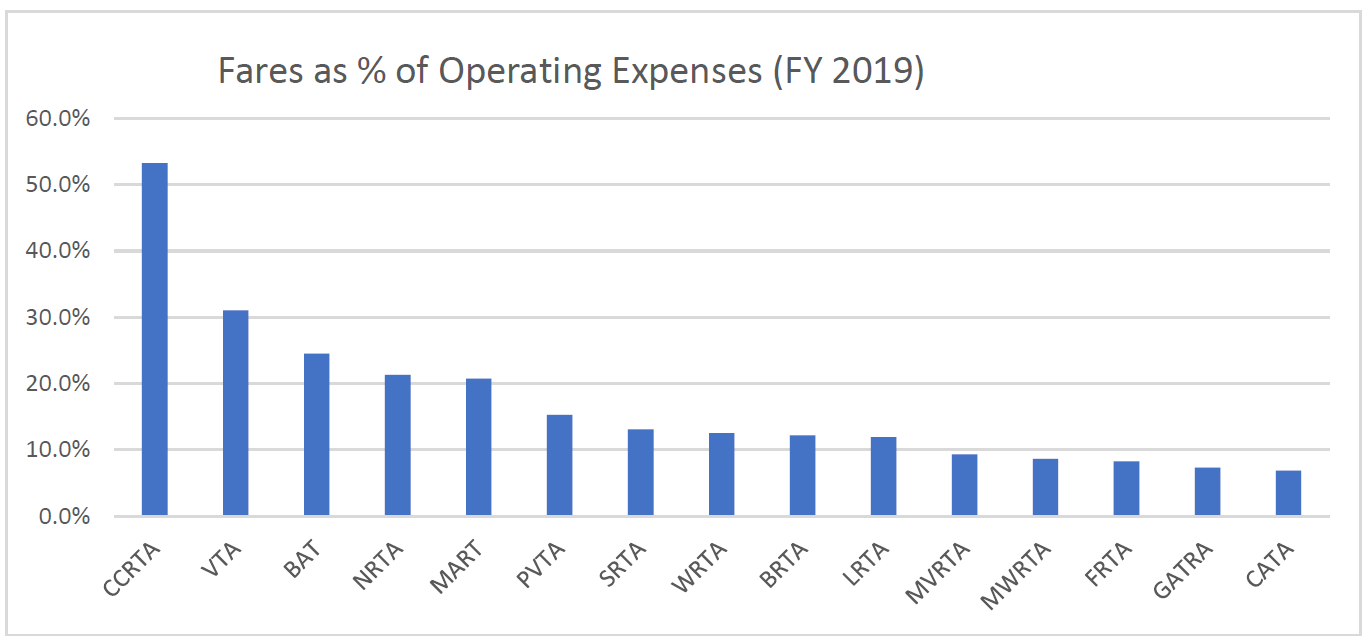

Let’s look at how much RTAs collect in fares and how that compares to their overall budget (see the graph below). Out of 15 RTAs, 10 of them cover 15% or less of their annual operating expenses through fares. That includes the RTAs serving some of the largest—and poorest—cities in the state, including Pioneer Valley (PVRTA), Worcester (WRTA), Merrimack Valley (MVRTA), and Southeastern (SRTA). It also includes RTAs serving the poorest rural areas, such as Franklin County (FRTA).

Meanwhile, the RTAs at the high end of the graph are the unusual ones. Martha’s Vineyard (VTA) and Nantucket (NRTA) serve year-round island residents and seasonal tourist populations, for whom transit is particularly convenient and efficient. Cape Cod (CCRTA) and Montachusett (MART) have had success with on-demand transit programs that may tap into a higher-income customer base allowing for greater fare collection. Finally, Brockton Area Transit (BAT) serves a very compact region—mostly the City of Brockton—so it can serve its coverage area quite efficiently.

But for two-thirds of the RTAs, the question that may leap to mind after seeing this graph is: why do we collect fares at all?

Furthermore, the graph shows gross fare revenue, which doesn’t account for the expense of collecting fares. Each RTA may have a good sense of their own internal operations, but there is no public statewide information that breaks down that figure in a useful way. Analysis should account for direct, indirect, and future costs.

Direct costs include security vehicles for transporting cash, people who count the money, and the expense of the fareboxes themselves. But other expenses may not be so obvious. For example, perhaps 30% of customer service time may be spent helping riders navigating fares and existing discount programs. If the RTA no longer collected fares, could they reduce staff or use those staff hours for something else?

In addition, the indirect costs of fare collection are significant. One of the principal job stressors and time wasters for bus drivers involves negotiating with passengers about fares and payment. Not collecting fares at all can significantly reduce travel time and may be one of the easiest ways to improve service for all riders. Right now, some riders must use cash and need exact change. Others never carry cash and need a contactless payment system. By eliminating these obstacles, there may be entirely new groups of customers willing to try the bus. Another positive side effect would be that fare evasion would no longer need to be criminalized and enforced, avoiding those conflicts and costs entirely.

Finally, future costs should be considered. Most transit authorities will have to adopt new fare collection systems in the next few years. What will the capital, training, and maintenance costs be, and how much would be saved if that need was simply eliminated?

Clearly RTAs net less than their gross fare collection receipts. Depending on the geography and type of service, the total cost of fare collection could be a large percentage of fares themselves. If an RTA collects $2 million in fares but spends $1 million in direct and indirect costs from fare collection, it may not cost as much as we think to go zero-fare.

According to pre-pandemic 2019 figures, the gross amount of fares collected by all 15 RTAs totaled $44 million combined. In FY2020 with four pandemic months and a 25% drop in fare revenue across RTAs, that figure is about $33 million, and the FY2021 total will be far lower. But let’s stick to a pre-pandemic year for comparison to other state programs. $44 million would be well below the state’s film tax credit which is estimated to cost between $56-80 million annually, and it would be similar to the cost of state police personnel assigned to MassPort, at $45 million. So it’s certainly a significant figure, but seems remarkably low to provide free bus service to more than 50% of Massachusetts residents. It’s hard to imagine a comparable state investment that could impact so many lives in such a direct, positive, and dramatic way.

Not surprisingly, there are complicating factors. One is that according to the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), paratransit service cannot cost more than double that of normal service. That means if the buses are permanently free, then paratransit must also be free. We need to understand what that cost looks like, because it seems to vary wildly from RTA to RTA. We also need to explore whether there are ways of designing zero-fare programs that can minimize this issue.

A second dilemma concerns how to best spend transit funding. Currently, most RTAs want to spend new dollars on extending bus service into evenings and weekends, increasing the frequency of buses on key routes, and expanding the service area. These are certainly important goals.

But this is not a zero-sum game. We shouldn’t have to choose between better service or fair fares. The Legislature needs to accomplish both through more sufficient RTA funding.

As the saying goes, budgets are about values, and RTAs are no different. There should be a robust public dialogue in each region to prioritize transit investments, and local riders and elected officials should have a prominent voice in those decisions. The state, as a principal funder of regional transit, also has a role in safeguarding the interests of the whole Commonwealth to accomplish important transportation, housing, and climate goals.

The question is: what regional transit strategies will achieve a multimodal future most quickly and effectively?

We think that there are some unique and profound benefits to investing in zero-fare bus programs for fixed-route service compared to other potential investments.

First, we believe that zero-fare programs have proven to be the most impactful initiative that medium-sized transit systems can do to boost ridership.

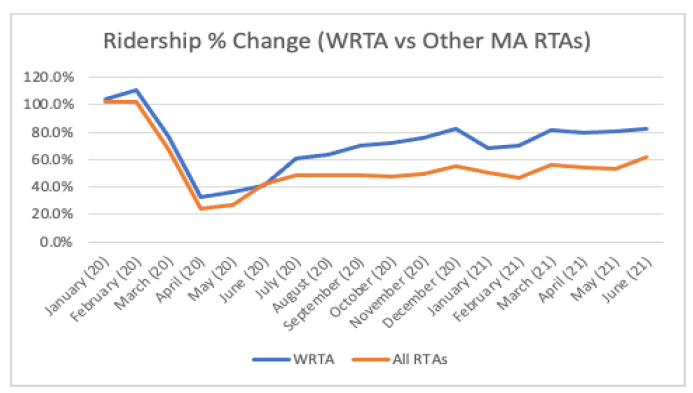

We can look at the results from such programs. For example, Lawrence grew its ridership on three free routes with minimal marketing by more than 20% in three months. Olympia, WA increased ridership systemwide by 35% by only its second month, and Corvallis, OR achieved a 40% increase over the course of its first year. During the pandemic, the Worcester RTA retained about 40% more of its ridership compared to other RTAs during the pandemic, presumably because of its zero-fare program instituted in March 2020 (see chart below).

Those increases seem to go well beyond the ridership gains that could be accomplished by extending service hours or even adding a new route. Since ridership remains low and fare collection is already depressed because of the pandemic, implementing zero-fare programs for a year or two—subsidized by federal stimulus funds or offset by the state—could be a good way of rebuilding ridership. There is plenty of service capacity available to absorb new customers. This would also provide time to evaluate whether zero-fare is a good long-term option for some RTAs.

Second, it puts money directly into the pockets of many of the poorest seniors and families in Massachusetts. The best data we currently have is from the City of Lawrence, which conducted face-to-face interviews with 300 bus riders (many of them Spanish-speaking) on their free routes before the pandemic. They learned that 90% of the people using its free bus routes have annual income of less than $20,000. Many of them are seniors on fixed income or essential service workers. Zero-fare transit can represent $60-100 saved each month that can pay for food and medicine. Or to take a job versus not taking one, or going to the doctor for critical appointments, or not having to walk 4 miles round-trip to a grocery store. These are all examples of real stories collected during the Lawrence interviews.

Zero-fare bus programs empower Massachusetts residents who need it most. Not only does it build wealth by connecting people to jobs, goods, and services, but it targets the transit-dependent precisely. At the same time, it provides a wonderful benefit available to every resident, so there is no shame or stigma. There is no government waste or regulation, no staff to hire, no contracts, no dilution of impact as with tax credit programs. There is literally zero overhead and in fact, it makes transit operations leaner. 100% of the investment will reach its targeted beneficiaries. After twenty years of public advocacy, I cannot think of a more efficient and cost-effective way of helping our communities.

Third and finally, zero-fare programs offer a clear path to building a culture of transit throughout the state. It has generated more excitement about public transportation in smaller cities than anything else in the last fifty years, as indicated by the explosion of activism in the Worcester area this year by riders and elected officials to retain its zero-fare program.

Residents, drivers, and businesses love fare-free buses. Where it has been implemented, feedback indicates that it becomes the most popular thing that the transit agency has ever done. What else can generate actual love for transit systems? This kind of fervent support translates into the kind of mobilized constituency and broad public interest that RTAs otherwise lack to secure transformative levels of investment.

The pandemic has created an opportunity to spread our state’s wealth more equitably by catalyzing economic development in cities and towns outside Metro Boston. More people enjoy hybrid office environments and want to re-orient their lives closer to their families, as indicated by the hot housing market in Gateway Cities and elsewhere.

But in order for this moment to last, Gateway Cities need the kind of dense development of jobs, housing, and services that can only be supported by a strong transit system. Although many RTAs see zero-fare policy as a frightening budget challenge, the biggest benefit may be the creation of a much bigger transit constituency, a vocal, mobilized ridership eager to advocate for the resources that the RTAs need to grow.

Some legislative recommendations on zero-fare programs for RTAs:

- Encourage RTAs to adopt temporary (12-24 month) zero-fare programs to build post-pandemic ridership by appropriating state ARPA stimulus dollars to reimburse the cost of lost fares as a result of such programs. Using 2019 fare levels, the maximum cost if all 15 RTAs were to participate for two years would be $88 million. The cost is likely to be less. This would enable RTAs to dedicate their own federal stimulus dollars to service improvements.

- Beyond this pilot period, match local funding 1-to-1 with state funds for Gateway Cities that deploy municipal dollars to subsidize RTA bus fares in their communities, as Lawrence currently does with the MVRTA. A state match for these particular communities makes sense because they house a high percentage of low-income residents, essential workers, and people of color. Doing this provides RTAs with more flexibility to work with their communities to make their system partially fare-free.

- Subsidize studies for those RTAs that want to conduct detailed cost-benefit analyses on their fare policy, including going fare-free, and undertaken in partnership with a third party.

- Eliminate farebox recovery ratio as a performance metric (as included in the RTA Advancement Bill (S.2277/H.3413) and allow RTAs to set their own fares at levels appropriate for their communities and ridership.

Thank you for your attention. Please do not hesitate to contact me via phone or email below if I can be of any assistance.

Sincerely,

Andre Leroux

Consultant, Transformative TOD

MassINC

To read our testimony on transportation revenue bills, click here.

To read our testimony on the Regional Transit Authority (RTA) Advancement bills, click here.