KELSEY CLARK, A SENIOR at Greater New Bedford Regional Vocational Technical High School, is showing a visitor work from her graphic design portfolio. There is a pointillism-style poster she drew for assignment to promote a rock concert (she says it left her practically drawing dots in her sleep). A brightly colored infographic poster that she designed documents the benefits of physical activity—a natural topic of interest for the three-sport varsity athlete who competes on the school’s soccer, basketball, and lacrosse teams.

A friendly 17-year-old with an easy smile, Clark says she loves the mix of traditional academics and career-focused technical education at the school, and she has excelled at both.

“It’s the perfect fit for me,” says Clark, who was the salutatorian—second in her class—at the Catholic middle school she attended before arriving at New Bedford voc-tech in 9th grade.

Last summer she had an internship through the school designing brochures in the marketing department at St. Luke’s Hospital in New Bedford. In the fall, she is heading on a merit scholarship to Stonehill College, where she plans to pursue her passion for art and design with an eye toward working in marketing or advertising.

Clark doesn’t fit the preconceived idea of a vocational school student. But today’s vocational-technical schools in Massachusetts are also a far cry from the “dumping ground” they were often characterized as in the past, places to steer non-academically oriented kids who were struggling to keep up in school.

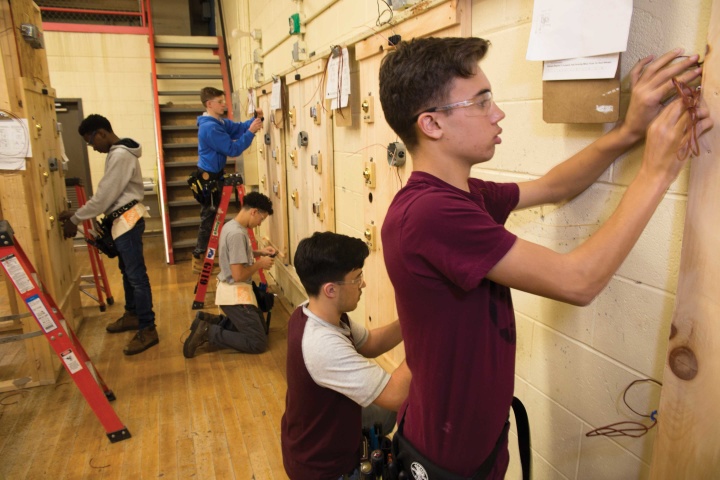

Vocational schools are, in fact, emerging stars of the state’s education system. They have been on a steady rise that has many of them now outperforming their conventional counterparts on standardized tests and graduation rates. Today, they find themselves in the sweet spot of education thinking, as terms like “career pathways” and a new appreciation for applied learning that might connect to future employment take hold. Vocational schools are drawing thousands of academically solid students, and sending many of them on to four-year colleges as well as to two-year community colleges and other post-secondary training programs.

But their success has given rise to a troubling situation that would have been hard to imagine years ago: The demand for seats at vocational schools is now so great that some of the students who in the past would have gravitated to them—those drawn to a particular trade or to the idea of hands-on learning, or not overly engaged by full-time “book learning” in a conventional school setting—are getting turned away.

State regulations allow vocational schools to admit students on a competitive basis, and critics say that is screening out the very kids who might most need the applied learning of vocational schools to spark their interest in school and stay on track.

“The right kids aren’t getting in,” says Scott Palladino, principal at Wareham High School on Cape Cod. “The kids who need to learn a trade, those hands-on kids, aren’t getting accepted.”

“We talk about no child left behind,” says Haverhill Mayor James Fiorentini. “We are excluding thousands of kids from getting the education they deserve by running our voc schools like elite prep schools.”

That may be overstating things. Vocational schools enroll plenty of kids who are in the middle of the academic pack, or who lag behind it. And the schools, taken as a group, enroll a higher percentage of special needs students than Massachusetts schools overall. But there is also more than a kernel of truth to what Fiorentini says.

Some vocational schools have very low enrollment of special needs students and English language learners, a pattern for which some charter schools have drawn criticism. And vocational schools have become a particularly favored choice for middle-class families in urban communities where district high schools struggle with high dropout rates, disruptive students, and other challenges.

Many of the schools have solid academic offerings and boast state-of-the-art facilities for vocational programs, supported by a state funding formula that sends voc-tech schools about $5,000 more per pupil than district high schools.

While some vocational schools have unfilled seats, many of those serving the state’s Gateway Cities—former industrial centers such as New Bedford, Worcester, and Fitchburg—are now oversubscribed. According to a report issued last year by the Massachusetts Budget and Policy Center, 3,200 students were on waiting lists at Massachusetts vocational schools for the 2015-16 school year. Gateway Cities account for roughly one-quarter of all public school students statewide, but they were home to 53 percent of those unable to land a spot at a vocational school.

The high demand for seats has created what a 2016 report from Northeastern University called a “peculiar paradox” in Massachusetts vocational education.

“Some still think that these schools are reserved for students who cannot succeed in the state’s comprehensive high schools,” said the report. But vocational schools are, in fact, now in such demand, it said, that they are leaving behind students “with lackluster academic or disciplinary records, often with fewer family resources, who have historically benefitted the most from career vocational education, and who now must compete for vocational school slots with better-prepared students—many of whom are college-bound.”

“It’s a Catch-22, there’s no question about it,” says David Ferreira, the executive director of the Massachusetts Association of Vocational Administrators, a statewide organization representing vocational school leaders. “What’s clear is some of the youngsters who used to be able to get into voc schools no longer get in because it’s ability-based and is based on a set of standards approved by the Department of Education.”

Mitchell Chester, the state education commissioner, says, “I think of it sometimes as, our voc schools are victims of their own success.”

VOC RISING

If there was a single turning point that sent the state’s vocational schools on their upward trajectory, nearly everyone agrees it was passage of the 1993 Education Reform Act. A 1984 federal measure, the Perkins Act, pushed vocational schools to beef up the academic side of their program. But it was the state law passed a decade later that provided the clear incentive for vocational schools to take academic outcomes more seriously. The law brought millions of dollars in new education spending, but also demanded accountability for results, introducing the MCAS exam in math and English, which all public school students in the state had to pass in 10th grade to receive a high school diploma.

Many vocational school leaders reacted with alarm and lobbied against being held to the same standard. Their schools were not focused on academics, they said, and their students were not, for the most part, looking to continue their studies beyond high school. But state officials held the line, insisting that there would be no exemptions from the new graduation requirement.

For vocational schools, rather than proving to be their undoing, introduction of the new graduation requirement became a defining moment that led them to dramatically ratchet up their academic programs and standards, moves that have a lot to do with why the schools are in such demand today.

“What looked like a curse ended up being a blessing,” says Robert Gomes, community outreach coordinator at Greater New Bedford voc-tech. “We had to meet the challenge.”