In Suffolk DA’s race, calls to coalesce

Groups urge blacks, progressives not to split their vote

WHAT HAD BEEN a strong undercurrent in the Suffolk County district attorney’s race is now becoming an open topic of conversation – and consternation: The fact that candidates with similar profiles in the five-way Democratic primary could split the vote and hand the election to a candidate who wins far less than majority support.

That’s the thinking behind efforts by groups of black and progressive voters to coalesce around a single candidate. But the calls for unity have produced anything but that, with some candidates denouncing the moves as strong-arming tactics aimed at short-circuiting voter choice in the race for an open seat.

Voting reform advocates say the backlash and tension being injected into the race are natural byproducts of a broken electoral system, one in which too many races are decided by small pluralities that don’t reflect the will of the majority. They are pushing for Massachusetts to adopt a system called ranked-choice voting, now in place in Maine, which proponents say would eliminate the perverse incentives of the current system that can sometimes pit people with similar views against each other.

Rachael Rolllins: Is she the best hope for progressive and black voters in the Suffolk DA’s race?

In Boston’s black community, the controversy is being stirred by an effort led by former state senator Dianne Wilkerson, who has organized several meetings over the last few months aimed at settling on a single minority candidate for the community to get behind.

Three of the five Democratic primary candidates come from minority communities: Rachael Rollins, whose mother is black, Evandro Carvalho, a Cape Verde native, and Linda Champion, the daughter of a Korean mother and African American father.

Wilkerson and others involved in the effort say they are simply trying to leverage the community’s clout and increase the chances of electing a minority candidate to an office that plays a huge role in day to day life in Boston’s black neighborhoods.

“I am actually surprised that there would anybody who would have an issue with the idea that we can’t have three candidates of color,” said Wilkerson, a one-time rising political star whose career was pockmarked with scandal and who was sent to federal prison in 2011 for two years on corruption charges.

Wilkerson points to the 2013 Boston mayor’s race, when six minority candidates vied in the 12-way preliminary race. The top minority vote-getter, Charlotte Richie, missed the runoff for the two-way final election by placing third. “There has been a consistent feeling of missed opportunity in the mayoral race and that we can’t do that again,” she said.

Linda Champion says voters, not self-appointed “gatekeepers,” should choose the next DA.

Champion, a former Suffolk assistant district attorney, says Wilkerson is leading a rigged process, one that had that settled on Rollins as the candidate to back from the start.

“The candidate has already been selected,” Champion said, ripping into the idea that “gatekeepers get to pick and anoint” who the black community should support. She says people tied to the effort have approached her following candidate forums and told her leaders in the city’s black community want her to quit the race.

“The system is corrupt and rigged against political outsiders and it needs to end,” Champion wrote in a lengthy Facebook on Monday that ripped Wilkerson.

Boston once had a group in the black community that tried to play the “gatekeeper” role Champion decried. The Black Political Task Force was active from the 1970s until the early 1990s, offering endorsements and calling on black voters to coalesce around chosen candidates.

Since its demise, there has been no entity in the city’s black community to play that role.

The new group, which has dubbed itself The Black Collective, sent the three minority candidates questionnaires to fill out last week as part of its endorsement process. “It’s an attempt to pull all of us together and push in one direction,” said former state representative Marie St. Fleur, who has been part of some of the group’s meetings. The organization plans to hold a fundraiser next week for the candidate they decide to back.

Wilkerson and St. Fleur both said they are supporting Rollins, but Wilkerson said supporters of Carvalho and Champion have attended meetings of the group. St. Fleur said she would shift her allegiance to another candidate if one wins the group’s endorsement. Wilkerson and St. Fleur both said there will be no call for anyone to drop out of the race, only a message encouraging black voters to rally around a single candidate.

At this point, however, a Rollins endorsement seems a foregone conclusion: Neither Champion nor Carvalho planned to meet with members of the group for endorsement interviews this week.

“This is kind of like the old way of doing business,” said Carvalho, a two-term state representative and former Suffolk assistant district attorney. “It’s unfair and it’s biased. We’re a different community now.”

He linked his opposition for the effort to the reform many are talking about for the DA’s office. “Some of the things we’re challenging are fairness with the system and backroom deals and biases,” he said of the justice system. “We want more transparency. Based on the values I stand for, I’m not going to submit to special interests. I answer to the people of my community.”

Evandro Carvalho, chatting with a voter following an April candidates’ forum in Jamaica Plain, says the endorsement process launched by group of black leaders in Boston is “unfair and it’s biased.”

Kevin Peterson, a veteran activist in Boston’s black neighborhoods, understands well the issue now roiling the community. In 2013, he led an ill-fated effort that called on several black candidates in the Boston mayor’s race to bow out in order to boost the chances of former state representative Charlotte Richie.

“I got my head handed to me,” Peterson said of the blistering criticism he faced over the move.

This year, Peterson is involved in efforts to raise the visibility of the DA’s race in Boston black community, but he’s steering clear of any effort to get behind a particular candidate. “There are difficulties with regard to the race being overcrowded with people of similar policy perspectives, but we’re OK to let that settle as it may,” he said of the DA’s race. “Our main focus is to galvanize and organize energy toward electoral engagement,” Peterson said of a nonpartisan church-led effort he is part of that is doing voter education canvassing aimed at turning out the vote for the DA’s race.

The pique expressed by Champion and Carvalho is understandable. But so is the argument that groups with common interests or views dilute their power when they spread their votes among several candidates.

That thinking is also driving an effort by a group of progressive organizations to unify behind a candidate in the race. The Justice for Massachusetts Coalition announced last week that it is backing Rollins, a former general counsel to the MBTA and state Department of Transportation.

Ziba Cranmer of the Jamaica Plain group JP Progressives, which is part of the coalition, said the goal was clear from the start of the DA’s race. “How do we align the progressive vote and not split the progressive vote and elect the least progressive person as a consequence,” she said, referring to Greg Henning, who has overseen the gang unit under outgoing District Attorney Dan Conley and is viewed by many as the front-runner in the race.

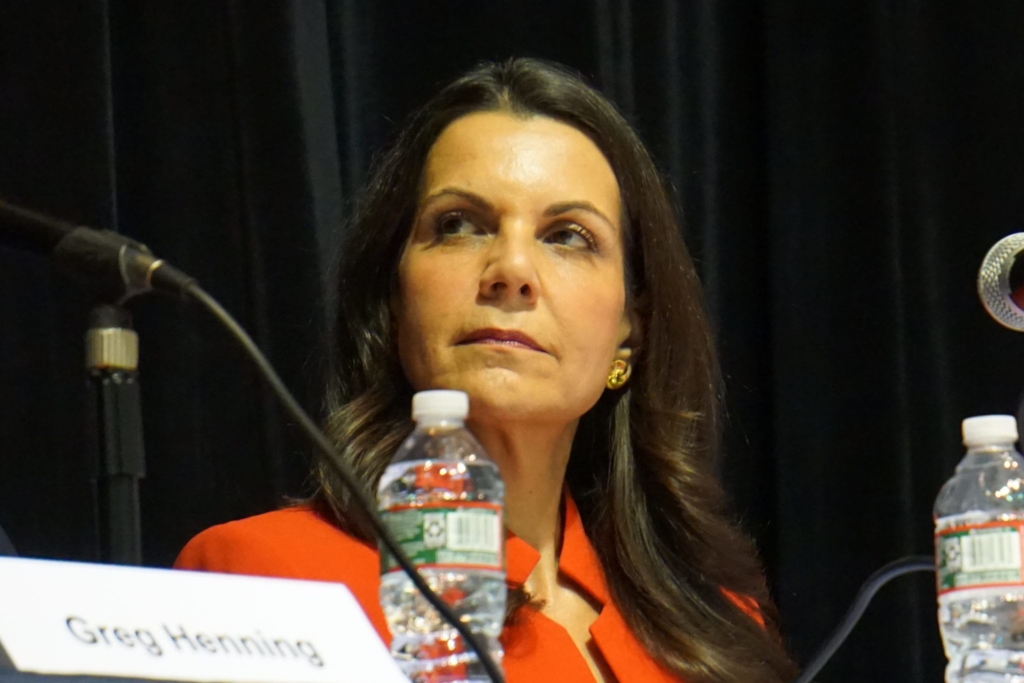

Greg Henning: The front-runner progressives are trying to catch.

The Justice for Mass. Coalition sent candidates a detailed issues questionnaire and wound up conducting a final round of in-depth interviews with Rollins and Shannon McAuliffe, a longtime public defender and former director of an anti-gang program with the nonprofit Roca.

“I’m incredibly honored and humbled, but invigorated,” Rollins said of her endorsement by the coalition of groups, which also includes Progressive Massachusetts, Progressive Democrats of Massachusetts, and Service Employees International Union 32BJ.

By some reckoning, it is McAuliffe who brings the strongest progressive profile to the race and can lay claim to being the boldest voice for change in the DA’s office. She’s the only candidate who has never worked as a prosecutor, and she’s the one candidate in the race who was gearing up to challenge Conley before the veteran DA announced he would not run for another term.

That lack of prosecutorial background might have been disqualifying at any earlier time. But it’s central to the argument McAuliffe is making for why she would be the true change agent at a moment of growing calls across the country to rethink criminal justice policies and practices.

Shannon McAuliffe says she’s “walked the walk” when it comes to advancing a progressive criminal justice reform agenda.

“I have to respect the decision that different groups make,” said McAuliffe. “But I feel like I’m the candidate that offers a fundamental difference and who has truly walked the walk as far as being progressive,” she said. “My values are layered into every choice I’ve made, every job I’ve had, every organization I’ve chosen to lead.”

Jonathan Cohn, a Boston resident active with Progressive Massachusetts, said he wound up concluding that Rollins had a better shot at pulling support from both minority neighborhoods and white liberal precincts. “I came away thinking Rachael has a better path to victory,” he said.

The jockeying taking place in the DA’s race is a familiar story line in Massachusetts elections. With such a heavy one-party tilt in many districts, races are often effectively decided in multicandidate primaries, where someone can prevail by winning just 20 or 30 percent of the vote. (There is no Republican running for the Suffolk DA post, though the winner of the Democratic primary will face an independent candidate, Michael Maloney, in the November election.)

That dynamic – and the pressure it puts on voters to coalesce around a single candidate who represents their views – could be eliminated by revamping the way Massachusetts elections are conducted, say voting reform activists.

The nonprofit group Voter Choice Massachusetts is leading the call for the state to adopt an approach known as ranked-choice voting. Under the ranked-choice system, voters rank candidates in order of preference. If no one garners a majority when first-choice votes are tabulated, the last place candidate is dropped from the field and the second-choice votes of their backers are distributed among the remaining candidates. That process continues until a candidate clears the 50 percent bar.