In Holyoke, arts education takes front seat

Non-profit helps integrate creativity into the regular curriculum

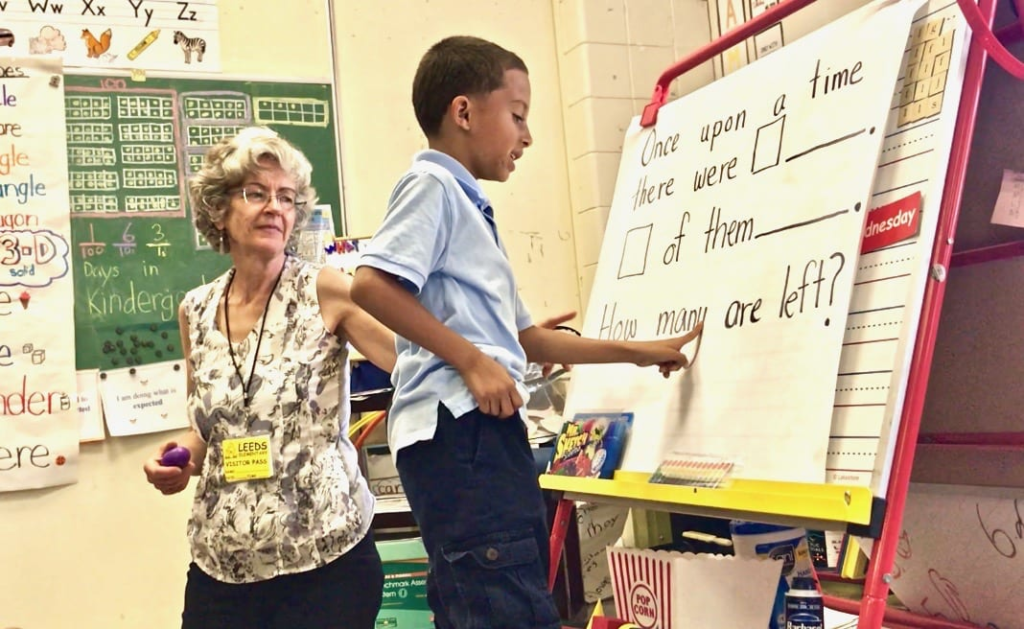

Dalializ, a kindergartener at the Kelly School in Holyoke, asks a question to an Enchanted Circle teaching artist.

SIX-YEAR-OLD JUAN patted an inflatable ball as he peered out of his blue-rimmed glasses. Which way to send the ball? What could he knock down?

Juan was playing “human bowling” in Kat Lorenzi’s kindergarten class in Holyoke. The objective was to get the ball to bounce off a few of his classmates, and figure out how many “human pins” he had knocked down from the total of 10. The kids understand there are 10 “pins” for the bowling ball to hit. He rolled the ball along the carpet, hit six, and those children sat down.

Ten minus six…

“Three!” said one child. “Four!” yelled several more, raising their hands. They huddled and decided on four.

Kate Carreiro said, “Yes, four.” Carreiro is a long-time “teaching artist” with Enchanted Circle, a nonprofit theater group that was contracted by the school district to help teach mathematics in six Kelly School classrooms, including Juan’s.

It seems like an unlikely marriage, theater and math. But in Holyoke, combining core curriculum with arts education is becoming a routine pairing. While cities across the country continue to cut arts education in schools, some Gateway cities in Massachusetts are bucking the trend and throwing resources at those programs.

Lorenzi, who studied early education and psychology at Westfield State University and graduated a year ago, swears by the method. “It’s whole grain learning,” she said. “It makes a life-lasting impression on bodies and minds. Having that concrete example to use your body on your learning is a way deeper impression than paper and pencil.”

Luis Soria, the Kelly School’s principal, said arts integration into the curriculum is not “art for art’s sake,” but an embedding of art into state learning standards. The arts integration closely aligns with what the instructors would be teaching the students anyway in their lesson plans.

Instruction varies by the grade—third graders gaining access to violins, and students in grades six to eight studying photography with a local photographer.

So far, the results have been encouraging. Kelly School was among the

lowest performing schools in Massachusetts two years ago and had a

very high suspension rate. Performance is improving, school attendance is up, and the out-of-school suspension rate has fallen from 16.8 percent to 11.4 percent.

“Absent the arts integration,” Soria said, “we wouldn’t have the successes we’re having now. I truly believe that.”

NEW TEACHING STYLE

Enchanted Circle started out in 1976 as a theater company that roved from Maine to Florida, as executive director Priscilla Kane Hellweg put it. Today, the company is based in Holyoke and has evolved into a multi-service arts organization that uses arts – including dance, music, visual arts, and media arts – as a teaching tool in classrooms and throughout the community.

Arts integration has a long history, but became a more respected method of teaching in the 1970s. Polish-born educator Harry Broudy was one of many to advocate for arts as a component of learning the usual classroom subjects such aa reading, mathematics, and science. Broudy’s belief was that traditional learning could be strengthened by the imagination brought to the learning process through arts.

“I thought I’d do this for a year or two after graduating college,” Hellweg said, laughing at the thought she has been with Enchanted Circle since 1980. “But I found my life’s work.”

The nonprofit has 14 teaching artists. Many of them are former or retired public school teachers. Some are bilingual, have multiple degrees, and specialize in more than one kind of art. Along with its work in Holyoke, Enchanted Circle has done extensive work in the Springfield schools. Both school systems embraced arts integration gradually over many years.

“It happened teacher by teacher, and got the interest of curriculum directors, then principals, then superintendents,” Hellweg said.

Kindergartener Angel reads from an assignment as Enchanted Circle teaching artist Kate Carreiro looks on.

Carreiro was a fifth-grade teacher in Holyoke when Hellweg came to her classroom in 1997 as a teaching artist. Carreiro was so impressed that years later she joined the Enchanted Circle board of directors, retired as a teacher, and became a teaching artist herself.

Enchanted Circle and Mount Holyoke College this summer are launching an institute out of the college, where K-5 teachers from across the country will train in arts integration. The idea is to teach reading, mathematics, science, and other academic disciplines using an arts component.

Arts integration isn’t a new concept, but has been used increasingly to teach core curriculum over the past 10 years. The Kennedy Center Turnaround Arts program is one of the pioneers of the concept, having offered arts integration opportunities for teachers nationwide and funding for those programs for more than 30 years.

One Kennedy Center teaching artist had 7th grade students act out their understanding of physical science laws like inertia, gravity, and density. Fourth graders in Virginia studied abolitionists by acting out the arrest of John Brown at the Harper’s Ferry arsenal in 1859, brainstorming how he and other historical figures might have spoken at the time.

DIRE STRAITS

In 2015, Steve Zrike was named the state receiver of the chronically low-performing Holyoke schools. He now oversees a $95 million budget, of which 1.9 percent currently goes for the arts. The more than 5,200 students in the district are over 80 percent Hispanic, and English-as-a-second-language learners are an added factor in the equation. Zrike has launched a task force to develop a three-to-five-year plan for arts programming in the schools, along with a strategy to come up with funding for the initiative.

Funding is a complicated issue. While integrating art into the school curriculum and the lives of students is an important goal in Holyoke, its value is not easy to quantify.

Over the last four years, Holyoke has seen a 20 percent improvement in the district’s graduation rate and a 23 percent improvement in the dropout rate. Forty-seven percent more students are enrolled in early childhood programming.

Art is not the sole explanation for the positive trends, but Zrike thinks it is a contributing factor. Many in Holyoke believe one of the biggest values of arts education is that it keeps students in school. The E.N. White and H.B. Lawrence elementary schools; the Kelly school, which includes elementary and middle school grades; and Holyoke High School all exceeded their goals for reducing absenteeism in 2018. The biggest improvement was at Lawrence, where 15.2 percent of students were chronically absent in 2018, as opposed to 26 percent in previous years.

Holyoke Public School Receiver and Superintendent Steve Zrike discusses efforts to boost arts funding in the school district.

Holyoke Mayor Alex Morse said the arts programming has been particularly effective in the early grades. “We’re seeing more student engagement and attendance numbers go up in elementary schools,” said Morse.

Jeff Riley, who was the receiver for the Lawrence school system before being tapped last year to become commissioner of the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, saw similar benefits by going beyond academics to provide students with more sports and arts options.

“We worked with the local Boys and Girls Club. Separately, some folks offered a rock band studio. We also had a good connection with Boston Children’s Chorus, which really worked with our students around vocal performances,” Riley said of his time in Lawrence.

Over Riley’s four-year tenure, the district’s graduation rate improved by 19 points. The percentage of students scoring proficient or advanced on the 10th grade MCAS test increased by 18 points in math and 24 points in English language arts.

Riley funded many of his initiatives by cutting the size of Lawrence’s central office staff. With his task force, Zrike is trying to find multiple ways to increase resources for the arts.

Zrike is well aware that students in school districts with more limited funding often have fewer options than the students in more affluent communities. “We’ve got to find ways to fund arts programming and enhance what we offer in our schools. While arts curriculum has remained mostly the same in suburban or affluent communities, the same can’t be said about communities of color,” he said.

“How do we leverage our annual budget resources, partners, the community assets to create minimally the experience we want every child to have around the arts? We have to define what that is and use whatever resources we have and match to that definition,” he said.